Dear game developers, you may remember Sebastian Standke and me – Christian Huberts – from our Call for Papers or the continued list of atmospheric games on this blog. We are still working diligently on the game studies anthology »Zwischen|Welten – Atmosphären im Computerspiel« (Engl.: »Between|Worlds – Atmospheres of video games«), based on the German philosopher Gernot Böhme’s concept of a new aesthetics. We use his term of the atmosphere as an research object and instrument for the game studies. Not only are we curious about the theory and perception of atmospheres in video games, but also about their practice and production. That’s why we have a favor to ask you. We’d like to hear your opinions, your theories and your strategies as aesthetic workers:

- What is your definition of atmosphere?

- How did you become aware of the atmospheric potential of video games?

- How do you address the production of atmosphere in your game design?

Please submit your answers (max. 5,000 characters) to atmosphaeren@googlemail.com [Edit: nicht mehr aktiv] till 30 June 2013 (just keep them coming!). And please also send us a atmospheric screenshot of one of your games or give us permission to use one from your press material. We’d like to publish your answers here on this blog and a selected few in our coming anthology Zwischen|Welten (Engl.: Between|Worlds). A German version of this call for interviews can be found on Superlevel. We are looking forward to your answers!

»The new aesthetics is thus as regards the producers a general theory of aesthetic work, understood as the production of atmospheres. As regards reception it is a theory of perception in the full sense of the term, in which perception is understood as the experience of the presence of persons, objects and environments.«

Gernot Böhme, Atmosphere as the Fundamental Concept of a New Aesthetics

And now for your answers…

Interviews

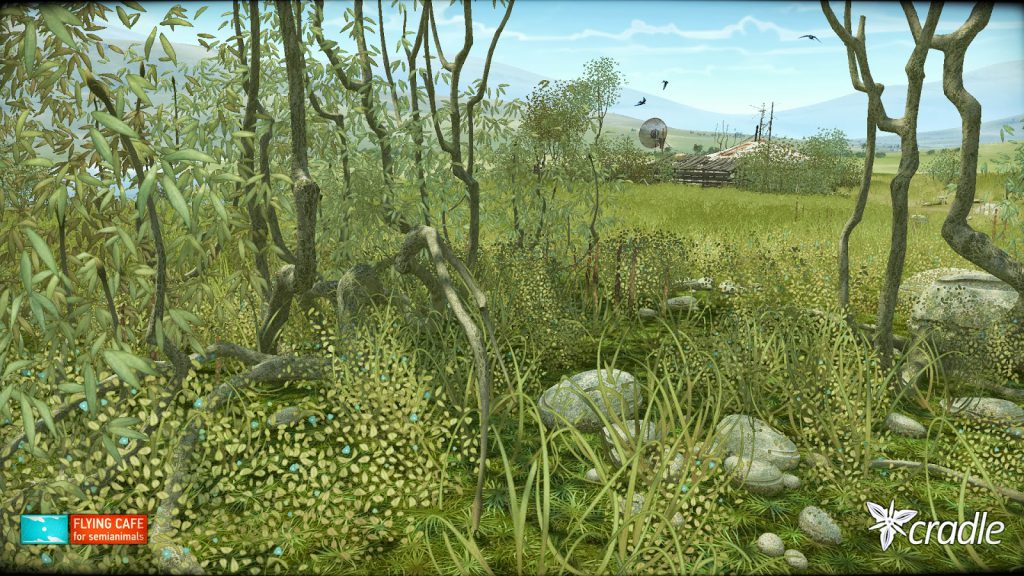

Ilya Tolmachevcra (Flying Cafe for Semianimals)

What is your definition of atmosphere?

Atmosphere is the ability of the game to evoke the player’s imagination and involve him in the gameplay as a creative co-participant in the narration. Starting from the moment when the game succeeds to persuasively hint that its virtual world is not limited by the borders of the scene and therefore encourage the player to think up events and locations left »behind the scenes« – the game acquires atmosphere. The atmosphere is a background enriched by the player’s imagination.

How did you become aware of the atmospheric potential of video games?

This occurred to me while playing Another World. The black panther showing up from behind the rock only to immediately hide again. Nevertheless, it did not disappear from the narration. You suddenly realize that you still feel its presence and involuntarily imagine how it moves around somewhere behind the scenes. This episode at the beginning of the game demonstrated a simple and grandiose atmosphere-creating instrument to us – the hint.

How do you address the production of atmosphere in your game design?

Firstly, we worked out the narrative events of the entire game universe in detail, leaving no logical gaps. Secondly, when the background story was ready, we took out most of the logical chains linking the »juicy« key events. To replace those ›removed‹ links, we designed indirect references (hints) and scattered them randomly around the game universe. Thus, we developed a virtual environment possessing the aesthetics of a surreal canvas, but able to turn into a realistic story with the player’s involvement.

Matthias Zimmermann

Was ist Deine persönliche Definition von Atmosphäre?

Ich definiere »Atmosphäre« als ein Komponentengemisch, das auf die fünf Wahrnehmungssinne des Menschen (Sehen, Hören, Riechen, Schmecken, Tasten) Einfluss nimmt. Die Visuelle und Auditive Wahrnehmung scheint mir dabei eine übergeordnete Rolle einzunehmen.

Wie wurdest Du Dir des atmosphärischen Potenzials von Computerspielen bewusst?

Die Mischung aus Ludologie, technischer Interaktion und Sounddesign bewirken beim User eine starke Immersion. Eine Gegebenheit von der ich gerne bei längeren Zugfahrten gebrauch mache. Eine Zugfahrt von beispielsweise drei Stunden reduziert sich durch ein ansprechendes Computerspiel zu einem magischen Moment, der mich meine Umgebung und die damit verbundene Zeit-Raumstruktur vergessen lässt. Ich verliere mich auf der Bildschirmfläche, die mir im Kopf eine räumliche Entität simuliert, meine Wahrnehmungssinne indirekt stimuliert und mich so in eine entsprechende Atmosphäre überführt.

Bonusfrage: Wie fließt Game-Design in Deine künstlerische Tätigkeit ein?

Mittels Programmen, die bei der Videospielentwicklung zur Anwendung kommen, entwickle ich im digitalen Raum großformatige Bilder, die ich im klassischen Sinne eines Gemäldes auf Leinwand drucke und auf Keilrahmen aufspanne. Meine Bilder zentrieren Fragen um Raumrepräsentation. Insbesondere meine letzten Arbeiten – eine 8-teilige Bildserie mit dem Namen »Die Raummaschine« – reflektieren den digitalen Weltenbau von Videospielen und referieren zugleich auf die Entwicklungsgeschichte der Videospiele.

Wie erzeugst Du Atmosphäre in Deinen Bildern?

Das Konzept der »Raummaschine« verstehe ich als ein Baukastensystem, dessen immer gleiche Hauptelemente wie Berge, Burgen, Seen, Raumschiffe variabel zu unterschiedlichen Landschaften und Atmosphären zusammengesetzt werden können. Ich gehe davon aus, dass ein Raum in sich schon eine Atmosphäre birgt, die jedoch unterschiedlich intensiv sein kann. Da es sich bei einem Gemälde um eine flächige Abbildung handelt, müssen die in der ersten Frage formulierten Wahrnehmungssinne auf visueller Basis dargestellt werden. »Die Raummaschine 6« zeigt einen Multiperspektiven-Raum, aus dessen Gegensätzen sich eine Atmosphäre bildet: Etwa der Feuerstrahl des Drachens, dessen Hitze mit der Kälte der Schneekugel und der gefrorenen Seefläche kontrastiert. Der Leuchtstrahl des Raumschiffs der die Landschaft verpixelt in einem CGA-Farbmodus darstellt. Hier wird neben dem visuellen Sinn indirekt auch der Tastsinn (warm und kalt) mit einbezogen. Licht und Dunkelheit bilden Schatten und strahlende Lichtquellen. Insbesondere bilden Schneekugel und Außenlandschaft einen Kontrast, da dessen Anordnung der Dinge eine unterschiedliche Dichte aufweisen: Während die Schneekugel die Stadt Tokyo in mehrere Ebenen komprimiert zeigt, deutet die Außenlandschaft eine verlassene Seefläche an, die durch den Schattenriss einer Industriekulisse – so wie ein Bergpanorama auf dem eine mittelalterliche Burg thront – begrenzt wird. Raumvolumen und die sich darin befindenden Element-Anordnungen erachte ich als wichtigste Atmosphären-Komponente. Um die Atmosphäre zu steigern wähle ich – im Vergleich zu einem Computerbildschirm – ein sehr großes Bildformat, dass mit 100 x 280 cm das Blickfeld des Betrachters quasi umschließt.

David Board (Stage 2 Studios)

What is your definition of atmosphere?

I’m afraid my answer isn’t going to be a very sophisticated one. I skimmed the Böhme article, but my art critic vocabulary is not terribly advanced. In point of fact, the thing that comes to mind when I think of »atmosphere« is the Calvin and Hobbes cartoon where Calvin imagines he is Spaceman Spiff, marooned on an alien planet with a dense atmosphere. The next frame cuts to him embarrassing his parents in a fancy restaurant as he screams »there’s too much atmosphere!«

My personal definition of atmosphere (in the artistic sense) would be a sense of place that evokes an emotional reaction. Atmospheres speak to the viewer in a personal way, suggesting at once both the familiar and the unusual, similar to the way we experience a distant memory or a vivid dream.

How did you become aware of the atmospheric potential of video games?

Through other video games. In particular, games like ICO, The Dig and Out of This World (Another World). These games gave me the ability to visit worlds that felt real, but at the same time were exciting, foreign, and bizarre. Not that I think atmospheric video games must be about science fiction. But sci-fi stories are a good fit for the underlying irony that I think is a part of successful atmospheric games.

How do you address the production of atmosphere in your game design?

I think it’s important to ground the game world in Earth-like environments, but changed in some small yet notable way. You have to start with the familiar to create believability, and then twist it in some small way. These small changes can actually create a big emotional response.

I also try to give a sense of character and personality even to inanimate objects. Buildings, trees, and hills should rest in the world as a human stands: with their weight generally on one leg more than the other. The human mind is constantly trying to identify faces in every object it encounters, and I simply try to nudge it towards this tendency.

Next, I think some of the most emotive events in our lives are recorded as discrete moments. When something dramatic or terrible happens, time slows down and we see the world in snapshots. I think this is why photographs can be so powerful. Even film shot at a slower frame-rate is commonly considered more artistic and emotive. With this in mind, I’m careful to design my game worlds such that I carefully control the angles at which the user will experience objects. I think it’s important that even as the player moves through the world there are moments (especially first encounters) that are directed by virtue of the paths and geometry of space to create compelling and memorable images.

At the risk of sounding like I’m taking »atmosphere« too literally, I suggest making use of physical atmosphere: often I actually show the air via fog, dust, or mist. Air filters light and conveys sound, so it’s important to show its effects when possible. I can’t explain why a simple ray of light streaming out of a storm cloud is so emotive. But it is, so I make use of this human reaction.

Finally, the only way I can truly make a personal connection with the viewer is to draw from personal experience. I take what is meaningful and emotive to me and use those elements to inspire scenes in my own art.

Klaus Vor der Landwehr (Turtle-Games)

Was ist Deine persönliche Definition von Atmosphäre?

Dabei handelt es sich um die Stimmung, die das Spiel bei den Spielern übereinstimmend hervorruft. Bei allen Spielern werden ähnliche Gefühle und Vorstellungen ausgelöst. Elemente wie Musik, Geräusche, Lichtmenge, Farben, Stil, Tempo, Perspektive usw. lenken und führen die Spieler in die jeweilige Stimmung und erzeugen so die Atmosphäre. Ich gehe davon aus, dass dem Einsatz dieser Elemente eine Grammatik mit universellen Regeln zugrunde liegt. Anders als bei einem Musikstück, Roman oder Film muss die Atmosphäre eines Spiels auch vom Handeln oder von den Handlungsmöglichkeiten des Spielers mit getragen werden. Beispiel: In Amnesia oder Slender kann der Held wegrennen, aber er kann sich dabei nicht umdrehen und auf seine Verfolger schießen, wie das in Shootern oft möglich ist. Wenn er es könnte, würde das der Atmosphäre schaden, die dadurch weniger bedrohlich und beängstigend wäre.

Wie wurdest Du Dir des atmosphärischen Potenzials von Computerspielen bewusst?

Mir ist diese Wirkung beim Spielen bewusst geworden, genauer gesagt während ganz bestimmter Situationen, die möglicherweise Folgendes gemeinsam hatten:

- das Fehlen von Action

- eine beschauliche Umgebung oder Landschaft

- subtile oder abwesende Musik

- ich hatte bereits Einiges in diesem Spiel mitgemacht

In diesen Situationen vergegenwärtigte ich mir nochmals das bisher Erlebte. Und in diesen Momenten ist mir die atmosphärische Wirkung des jeweiligen Spiels bewusst geworden.Ich kann mich etwa an folgende Spiel-Situationen erinnern:

Star Trek: Judgment Rites (Interplay, 1993)

Das Erster-Weltkrieg-Szenario, auf einem leeren Dorfplatz, wo getragene Musik gespielt wird.

Star Control II: The Ur-Quan Masters (Accolade, 1992)

So mancher Aufenthalt im Quasispace.

Conquest of Camelot: The Search for the Grail (Sierra On-Line, 1989)

In den Katakomben von Jerusalem beim Betrachten der Wandmalereien.

Wie erzeugst Du Atmosphäre in Deinem Spieledesign?

Ich gehöre einer kleinen Truppe von Indie-Entwicklern an, die kürzlich ihren Erstling, einen 2D-Space-Shooter namens Canopus, als Perpetual Beta veröffentlicht hat. Ich kann mich daher nur auf dieses Spiel beziehen. Wir konstruieren nicht vorsätzlich irgendeine Atmosphäre des Spiels. Und ich würde Canopus auch nicht zu den atmosphärischen Vorzeigespielen zählen. Allerdings wurde schon behauptet, das Gefühl eines Weltraumgefechtes werde stimmig vermittelt – und das ist durchaus unsere Absicht gewesen. Falls man also dieses Gefühl als Atmosphäre gelten lässt, würde ich folgende Elemente dafür verantwortlich machen:

- der detailierte Stil der Schiffe, Waffen, Geschosse usw.

- die tiefen, dynamischen Weltraumlandschaften

- das Effektgewitter samt Soundkulisse

- und nicht zuletzt die unbarmherzige Physik: Masse + Trägheit = Kollision

Stefan Köhler

Was ist Deine persönliche Definition von Atmosphäre?

Atmosphäre ist für mich die (oft nur augenblickhafte) Wahrnehmung der Summe aller Teilelemente einer Umgebung anstatt dem Fokus auf ein oder mehrere Teilelemente. Darüber hinaus entsteht Atmosphäre meiner Ansicht nach manchmal auch durch Kontextualisierung der Wahrnehmung des Spielers – entweder vom Spiel induziert oder vom Spieler selbst vorgenommen.

Wie wurdest Du Dir des atmosphärischen Potenzials von Computerspielen bewusst?

Das atmosphärische Potenzial von Videospielen wurde mir erst in der Herausforderung, selbst eine Spielwelt zu gestalten, wirklich bewusst. Genauer gesagt, verstellte der Blick für Details zunächst die Wahrnehmung des Ganzen, bis ich schließlich so weit war, mich ohne Optimierungsgedanken einfach über die Insel zu bewegen und am Ende meinen Lieblingsplatz zu finden.

Wie erzeugst Du Atmosphäre in Deinem Spieledesign?

Ich denke, man kann Atmosphäre nicht einfach und für jeden erzeugen, aber die Wahrscheinlichkeit einer solchen Meta-Wahrnehmung zumindest für Spieler, die dafür offen sind, erhöhen, indem deren einzelne Sinne überladen und dadurch unscharf werden, ob nun durch Teilelemente wie Video und Audio, die kohärente Informationen liefern, oder durch Kontextualisierung.

Benjamin Rivers

What is your definition of atmosphere?

Simply, it’s the manipulation of mood through direct and indirect cues (sound, absence of sound, colour palettes, etc.).

How did you become aware of the atmospheric potential of video games?

Games have always fascinated me primarily with their atmosphere. The very first game that had a real sense of atmosphere to me was Advanced Dungeons & Dragons (sometimes called Crown of Kings) on the Intellevision. Its sparse use of sound made it the first game to make me afraid.

How do you address the production of atmosphere in your game design?

With everything I do, I think of the mood first. There’s a lot a player can do to make a game better for him or herself when the mood is correct; they get more absorbed, they participate more acutely. To help achieve this, I spend a lot of time on sound, and I always make sure there are little pieces here and there that the player has to sort out on her own; once you force a player to start paying attention, she tends to notice all the little things you’ve put in there (the sound, ambient clues, etc.), and in turn becomes even more active.

Simon Flesser & Magnus Gardebäck (Simogo)

What is your definition of atmosphere?

Atmosphere is that thing that you cannot touch or see. It’s the sum of audiovisual impressions and communications. You simply feel it in your belly, when it’s there!

How did you become aware of the atmospheric potential of video games?

Tough question. I think mainly playing other games made me see the potential. Or perhaps the lack of atmosphere in some games made me want to challenge it.

How do you address the production of atmosphere in your game design?

Atmosphere is interesting, because you often have a clear idea of what kind of atmosphere you want to communicate. But as you go along, the game develops its own voice and sometimes it almost feels like it knows better than its creator what atmosphere it wants to communicate, and what it needs to create it. So, we basically try to mold it like clay, asking the game what it needs, until we understand what it is.

Connor Ullmann

What is your definition of atmosphere?

To me, atmosphere is the basic feeling a person has in a given environment. In video games, a dark room with chains, spiders, and blood would give a scary “horror” atmosphere, and the player (hopefully) feels that throughout the time they’re in the environment, provided the designer does a good job setting that atmosphere.

How did you become aware of the atmospheric potential of video games?

Immersion has always been the one feeling I look for when I play games, and atmosphere is the chief agent for immersing me as a player. Some players enjoy the competition of online play, others like the relaxed approach of casual games, and still others like the brief amusement of iPhone games on the bus – I’m a person who likes to sit down for hours with a single-player game that tries to sink me into its world. Some games that really gave me this immersion were: Minecraft (hardcore one-player survival mode), Dark Souls, Skyrim, and Amnesia: The Dark Descent.

How do you address the production of atmosphere in your game design?

The first page I turn to when I try to add some atmosphere to my games is to add lighting effects. Having that darkness on the edges of the player’s vision adds to the tension, curiosity, and downright beauty of a scene almost automatically. From there, I just try to thematically set up different scenes and make enemies/obstacles based around the theme. For example, in my adventure-action-RPG game Seedling, there is an ice dungeon where the player has to enter a cave from a blizzard that makes it very difficult to see anything clearly on the screen. They only have a small radius around them that stays clear of the white blizzard effects, and when the player tries to skate across ice and avoid enemies in that environment, it makes the player (if it works) feel vulnerable. Provided that is effective, they transition into the cave area has a combined sense of progress and relief. The grating wind sound disappears, the haunting music becomes easier to hear, and the player can see once again. This is one of my proudest points in the game, even if it goes by without most players even consciously noticing it.